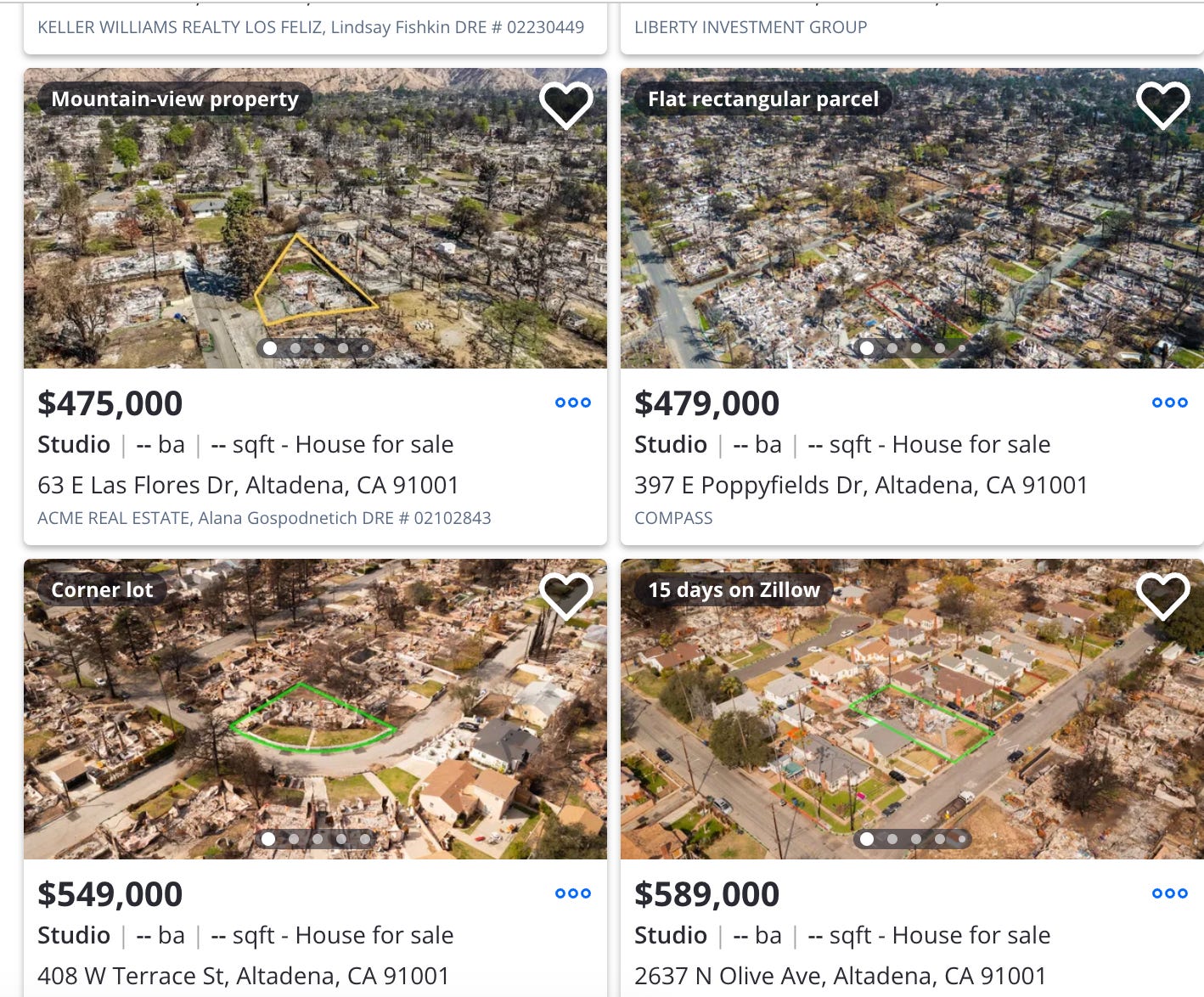

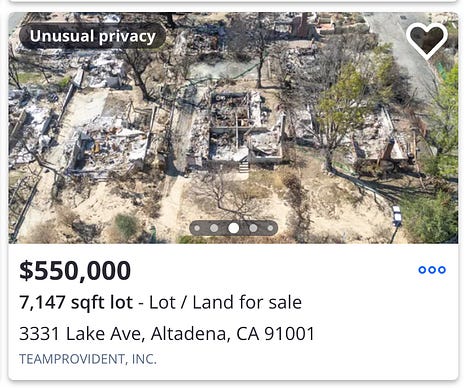

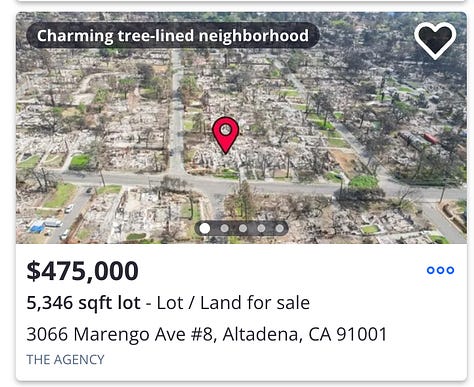

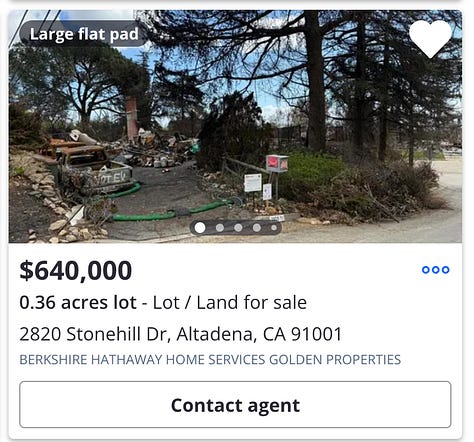

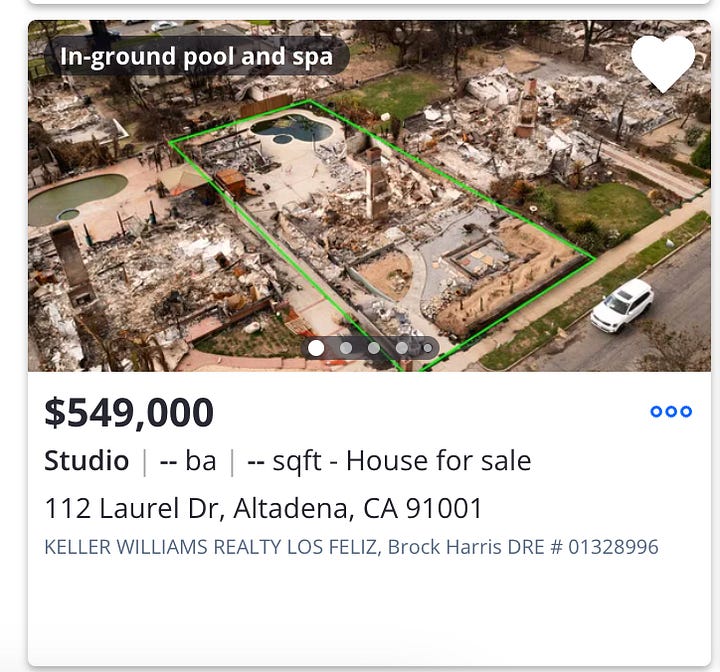

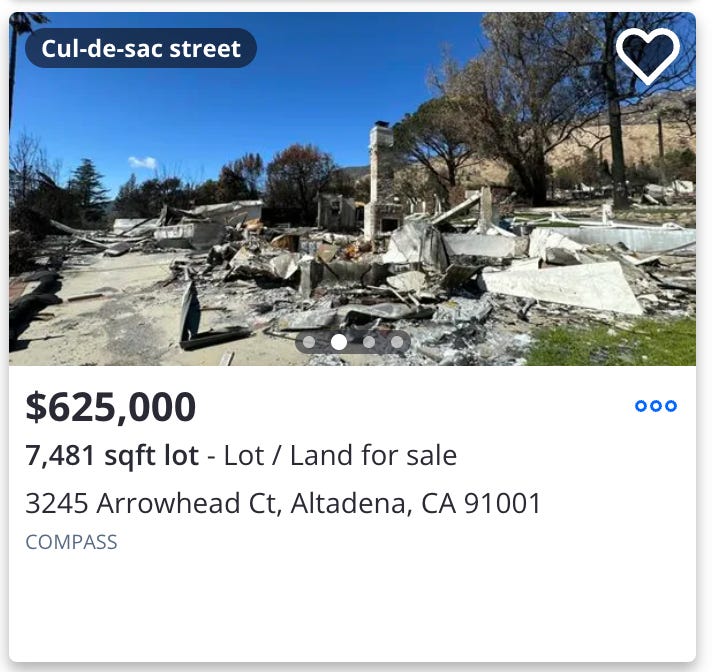

As of March 6, 2025, a Zillow search for homes in Altadena reveals approximately 50 active listings for burn-zone properties—charred lots, most without structures—priced at an average of $550,000, with the highest listing reaching $950,000.

Individually, the images are stark and unsettling. Viewed collectively, they become something else: a dataset of large-scale disaster rendered as a real estate inventory. The aesthetic dissonance is striking—scorched earth, detritus of lives, presented as investment potential; devastation recorded in pixels overlaid with vacuous, AI-generated marketing language.

The recasting of catastrophic imagery into marketing assets underscores the entanglement of crisis response with economic forces.

AI-driven platforms like Zillow, which employ proprietary machine-learning models to optimize listings, increasingly mediate our encounter with these sites of loss. The result is a jarring collision between tragedy and transactional language—an automated pluckiness imposed upon ruin, dissolving our capacity for sense-making.

In the aftermath of disasters, real estate platforms like Zillow function as both facilitators of recovery and conduits for displacement. Practically and politically, this raises urgent questions: To whom are these lots—former homes—being marketed? What kind of neighborhood will emerge from this process? How might civic leaders encourage a major platform like Zillow to mitigate, rather than amplify, existing inequities in housing access? And what role does it play in shaping the balance between rapid rebuilding and more deliberate, fire-safe reconstruction?

The frictionless, AI-enhanced nature of these marketplaces, in their surreal presentation of image-text pairings, plays a role in reshaping communities under the logic of both contextual and financial abstraction. The problem is not simply that owners are encouraged to quickly sell their properties post-disaster—an understandable and often necessary decision—but that the mechanisms of sale flatten the reality of loss and vulnerability into an impersonal investment opportunity. The listing language itself—“BLANK CANVAS!” “HOME OF YOUR DREAMS!”—illustrates how algorithmic market tools erase the trauma embedded in these landscapes. What effect does such a flattening have on our capacity to process the complexity of such an event. What alternative options might it preclude?

Beyond this, such platforms contribute to a broader pattern of wealth consolidation. Crises frequently serve as accelerants for ownership concentration, particularly in historically marginalized communities. In the case of Altadena, where Black home ownership far exceeded the national average, one must question whether these transactions truly allow local residents to regain footholds or if they facilitate an algorithmic acceleration of displacement. Rather than passively accepting the AI-mediated marketplace as inevitable, we could ask whether a different civic framework is possible—one that reorients post-disaster redevelopment toward ecological and reparative justice?

What if platforms like Zillow were accountable to climate-conscious urban planning, incentivizing fire-adaptive architecture, cooperative land trusts, or community land banks? What if real estate listings recognized rather than erased the environmental and social histories of affected areas? This is not to reject technology’s role outright but to argue that AI should be deployed with an awareness of the ethical dimensions of post-disaster markets. In its current form, the AI-driven marketplace may not be inherently malevolent, but it is still far from “neutral”.

Free Market Democracy

The counter argument, of course, is that while concerns about AI’s role in post-disaster real estate markets are valid, attempting to impose additional layers of mediation—such as mandatory state auctions, redevelopment restrictions, or procedural gatekeeping—risks exacerbating the very problems critics aim to solve. Market efficiency, including frictionless transactions, provides individuals with greater agency and access. Zillow, for instance, democratizes the marketplace by making listings public and widely available, broadening the buyer pool.

Introducing more bureaucratic layers—such as requiring compliance with climate-conscious planning frameworks or restricting who can purchase post-disaster properties—could have unintended consequences. Overregulation could lead to wealth concentration, as only large institutions with the necessary resources to navigate complex requirements would be able to participate. This would result in a different but equally troubling form of exclusion, wherein local ownership diminishes, and redevelopment is driven by corporate interests rather than individuals. The fear of AI facilitating displacement should not obscure the fact that increasing access to information and participation in real estate markets is, on balance, a positive development.

Moreover, AI’s role in real estate is not inherently dystopian. The strange, algorithm-generated descriptions of properties serve as a reminder that we have not yet fully entered a hyperreal simulation where human agency is erased. If anything, AI makes the absurdities of the market more visible rather than hiding them. While the current model of real estate exchange is imperfect, the alternative—a hyper-mediated, government-sanctioned redevelopment regime—could lead to economic stagnation and further entrench elite control. At its core, the market remains a mechanism for individuals to exercise their own decisions about property ownership, and the presence of AI does not fundamentally alter that principle.

Ultimately, what I find fascinating about the Altadena-Zillow marketplace example has less to do with technological inevitability but rather, about the social values embedded within such systems; that aesthetic conditions continue to train and hone our emotional registers.

These are not merely abstract concerns but pressing issues that will define the social and economic fabric of communities recovering from disaster, a circumstance all the more frequent in our climate-affected era. If AI and frictionless transactions accelerate displacement and wealth consolidation, then the market is not merely “democratized”—it is optimized for those with capital. Conversely, if intervention is too rigid or bureaucratic, the risk is an equally exclusionary system that stifles local agency. The challenge ahead is not to reject AI enhancement outright, nor to embrace it uncritically, but to rethink how it can be leveraged to support, rather than erase, the histories, vulnerabilities, and long-term resilience of communities.